Welcome

Welcome to PhilosophyStudent.org. Our goal is to open the door for novice philosophy students who are starting out with a deep curiosity and an unyielding desire, yet without knowing how best to grow, learn, and succeed in their studies. We are thus offering under one roof everything a novice philosophy student needs to know in order to succeed.

Philosophy sets itself apart from other disciplines by its promise to offer far more questions than answers. This takes some getting used to. These questions typically concern things most people take for granted. They are questions about existence, knowledge, mind,

reason, language, and values, among other matters. We, however, stand out from other philosophy books and websites by offering more answers than questions. No, they are not the answers to those big philosophical questions. Instead, they are answers to questions you may have—should have—about

what to do now that you are taking a class in philosophy. These answers will inform and enrich your academic study of philosophy. They will help you perform optimally in some of the most challenging and exciting coursework you will ever do, as well as guide and improve your academic performance, your test results, and the grades you receive on the papers you write.

Philosophy opens your mind and imagination, but insists on doing so in a disciplined manner. It is about learning more productive ways to think and to write and to argue, and in writing well and arguing effectively, to think with even more originality and greater clarity.

Here we ask and answer: What is philosophy? What are the branches of philosophy? What is logic and where does logic fit into philosophy? What is the history of philosophy? And then we answer the questions most germane to what you, as a student, will do in a philosophy course: How do you do philosophy? How do you create effective philosophical writing? What processes and skills are needed to write a philosophy paper? What are the

forms of philosophical writing? What strategic writing choices will best serve you in your class assignments? You will also find a concise but comprehensive reference section, containing the key philosophical terms and concepts, biographical essays on philosophers whom most philosophy professors consider most important, and a list of resources, including the books, websites, blogs, films, TV programs, and institutions you need to know about.

We hope we will succeed in introducing you to the many new concepts, approaches, and terms in philosophy. Starting out in Philosophy can be elating and yet bewildering: Where do I start, and what is my best path? We here want to offer the novice philosophy student—a way to avoid aimless wandering.

Another goal is to encourage—no, to recruit—more students to study and love philosophy. But if just one student ends up pursuing a life of philosophy because of something in this website, our work will have been worth the effort. For it surely will have made the world a better place!

WHAT IS PHILOSOPHY?

Philosophers ask questions and think about things that most people take for granted. So, philosophy is the study of general and fundamental questions about existence, knowledge, mind, reason, language, and values. Strange but true, it is the general and fundamental things that most people take for granted and therefore do not question. Why is this so? That is precisely the kind of question a philosopher would ask. Maybe you should consider asking —and answering—it in an essay for your philosophy class.

PHILOSOPHY AS METHOD

PHILOSOPHY AS METHOD

WHAT IS THE “SUBJECT MATTER” OF PHILOSOPHY

WHAT IS THE “SUBJECT MATTER” OF PHILOSOPHY

WHAT IS THE “SUBJECT MATTER” OF PHILOSOPHY

Branches of Philosophy

Philosophy embraces the most ambitious field of inquiry—the universe, including the self and everything both physical and metaphysical. It is impossible to list all the branches of philosophy, which are not only numerous but, since the realms of the mind defy taxonomy, so does philosophy. We can divide the major branches into two categories, the traditional and the modern.

AESTHETICS

EPISTEMOLOGY

ETHICS

PHILOSOPHY OF LAW

LOGIC

METAPHYSICS

NATURAL PHILOSOPHY

POLITICAL PHILOSOPHY

PHILOSOPHY OF RELIGION

BIOETHICS

HERMENEUTICS

PHILOSOPHY OF LANGUAGE

PHILOSOPHY OF MATHEMATICS

PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE

Logic

Logic is the systematic study of patterns of inference and is intended to clarify the underlying structure of “good” arguments. When we call an argument valid, we are not judging the truth or falsity of its premises or conclusion. We are evaluating its structure. An argument is said to be sound if it is both valid in argumentative structure and its premises are in fact true.

The language sketched above is better referred to as first-order predicate calculus, as the language only quantifies over (first-order) individuals. A stronger language, second-order predicate calculus, can therefore be constructed by allowing quantification over predicates —that is, second-order sets of individuals.

MODAL LOGIC

While both the predicate calculus and the modal propositional calculus may be seen as extensions of the basic propositional calculus, there are also a variety of formal languages intended as genuine alternatives. These non-classical logics typically argue that the logical connectives are governed by different truth tables (often with more than two truth values), or they impose additional constraints on what counts as a valid inference.

MANY-VALUE LOGICS

INTUITIONISM

RELEVANCE LOGICS

QUANTUM LOGIC

BASIC LOGICAL SYMBOLS

History of Philosophy

Because Western philosophy has proved most globally pervasive and has created a remarkably contiguous record—a genuine dialogue among philosophers over the centuries —our concise historical overview focuses on the Western tradition and reviews Middle Eastern, Indian, East Asian, and African philosophies only briefly.

THE PRE-SOCRATICS

PYTHAGOREANISM

THE ELEATIC SCHOOL

ATOMISM

THE SOPHISTS

CLASSICAL PHILOSOPHY

PLATO

ARISTOTLE

SKEPTICISM (PYRRHONISM)

CYNICISM

EPICUREANISM

STOICISM

RATIONALISM

EMPIRICISM

LIBERALISM

TRANSCENDENTAL IDEALISM

PHENOMENOLOGY

EXISTENTIALISM

THE FRANKFURT SCHOOL

STRUCTURALISM

MIDDLE EASTERN TRADITIONS

INDIAN PHILOSOPHY

PHILOSOPHIES OF EAST ASIA

AFRICAN PHILOSOPHY

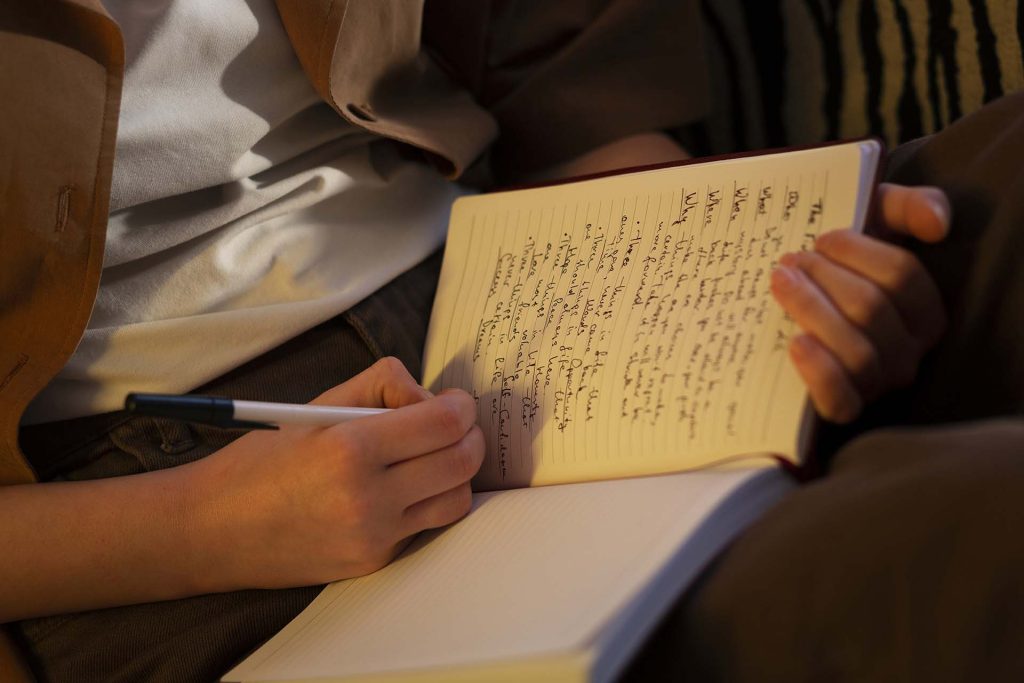

WRITING PHILOSOPHY

FORMS OF PHILOSOPHICAL WRITING

THE PERSONAL ESSAY

THE ESSAY OF ASSERTION

THE ESSAY OF AFFIRMATION

THE ESSAY OF REFUTATION

OTHER CATEGORIZATIONS OF PHILOSOPHICAL WRITING

THE EXPOSITORY PAPER

THE ARGUMENTATIVE PAPER

THE POSITION PAPER

PHIOLOSOPHICAL TERMS AND CONCEPTS

PHILOSOPHICAL BOOKS AND TEXT

BOOKS TO GUIDE NOVICE PHILOSOPHY STUDENTS

INTRODUCTORY PHILOSOPHY TEXTS

GUIDES TO PHILOSOPHICAL WRITING

INTRODUCTORY LOGIC TEXTS

There are plenty of good philosophy websites that will give you a good idea of what philosophers are (or were) doing and how they do (or did) it. Though this list is not exhaustive, it is fairly representative of what you’ll find (in English) elsewhere.

This list is organized alphabetically, by each philosopher’s last name. Given the number of excellent philosophers working today, this list is necessarily short, and almost entirely restricted to blogs and personal sites, rather than faculty pages. Nevertheless, the smattering of links should provide you with glimpses into the workings of these thinkers’ intellectual lives—glimpses not always possible from a book or scholarly paper.