How do you do philosophy? Unlike many of the questions asked in the name of philosophy, this one has a straightforward answer. You do philosophy primarily through writing. Now, if you are already behaving like a philosophy student, you should be challenging this answer. One highly plausible challenge is, No. You do philosophy by thinking. It is a fair point. I suggest, however, that you consider the following quotation, which has been attributed to everybody from the great British novelist E. M. Forster and the great American storyteller Flannery O’Connor to “an Anonymous Little Girl.” Whoever said it or said it first, it is brilliant and brilliantly provocative: “How can I know what I think till I see what I say?”

Epistemologists as well as neuroscientists, linguists, and semioticians (students of signs,symbols, and their interpretation) dispute the primacy of language, especially written language, in thinking. Rather than take up such disputes here, we can instead stake out an area about which most academics and others agree. Whatever role writing plays in the process of thought, writing at the very least facilitates and systematizes thinking. Writing gives it clear, symbolic form, and the symbols it creates—words, sentences, paragraphs, and so on—can be readily modified, arranged, and rearranged, thereby aiding thought. Let’s concede that some folks can play entire chess games, even multiple games, simultaneously and entirely in their heads. But let’s also admit that these are very exceptional people. The great majority of chess players, even good ones, need to see and move pieces on a physical board. The physical form of chess facilitates and systematizes play. For most players, it enables play.

So, let’s repeat. You do philosophy by writing philosophy. For the student taking a philosophy course, this significantly ups the ante of writing and writing well. For writing is not only the skill needed to take a course exam or to simply prove to the instructor that you have assimilated the course material, it is the course “material”—the substance of the course, the be all and end all of the course—in the same way that sitting down and playing the piano is the raison d’etre of Piano 101.

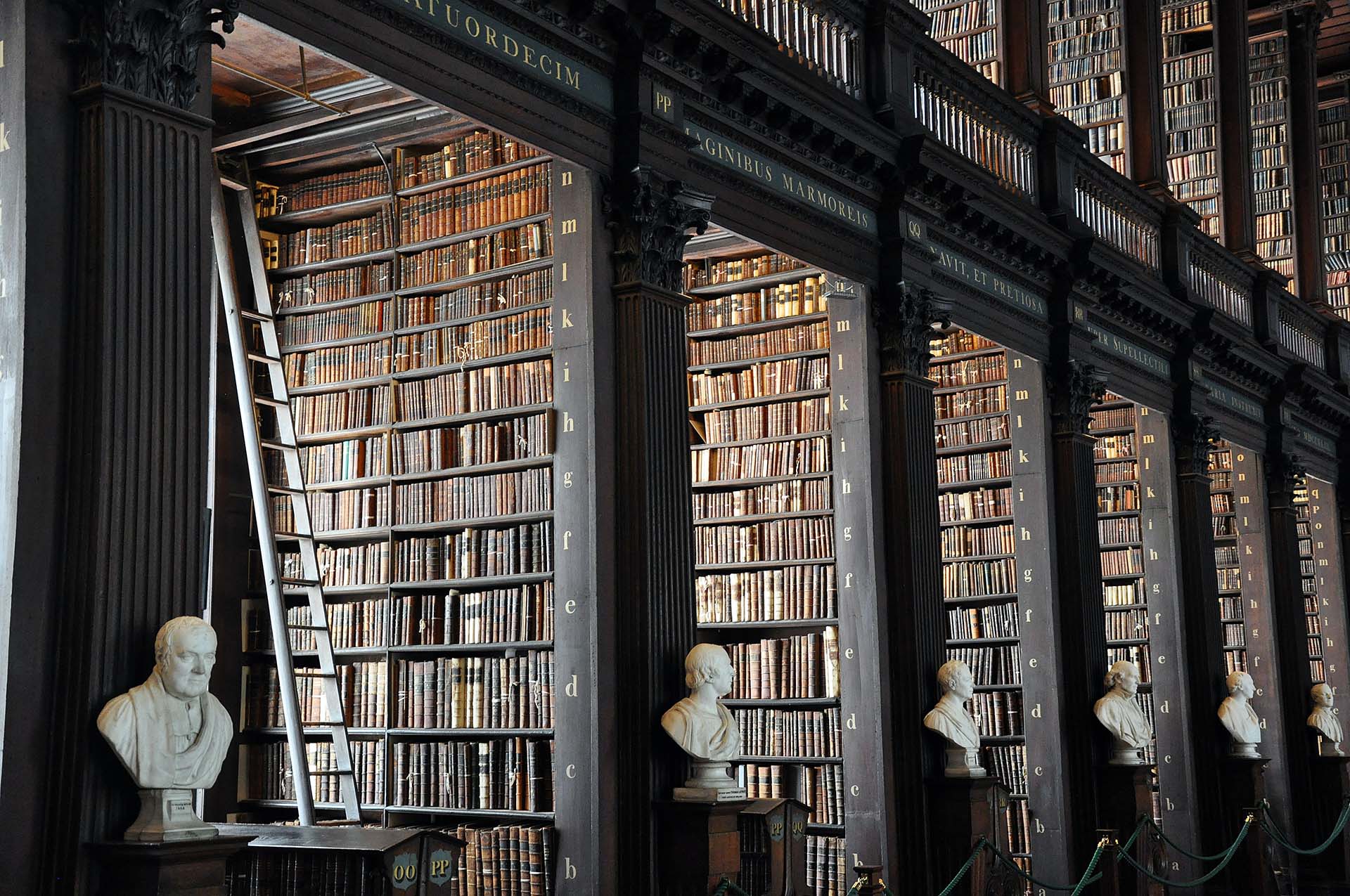

As instrumental as writing is to philosophy, it is for philosophers only the first of two indispensable processes. The second is publishing what has been written. Writing your thoughts in a private journal or diary may be deemed a philosophical process, but it is not practicing philosophy. Sharing what you have written is essential to philosophy because philosophical discourse is not a monologue but a dialogue, a global exchange and interchange with the community of philosophers. In this, philosophy resembles modern science, which requires researchers to publish their hypotheses and experimental results so that they can be reviewed by others in the field, who can also set out to replicate results and thereby support

or question or even refute the published results. While the work of philosophers is rarely supported by experiment, it still must be subject to critical discussion, suggested correction or elaboration, and even outright refutation.